Preview

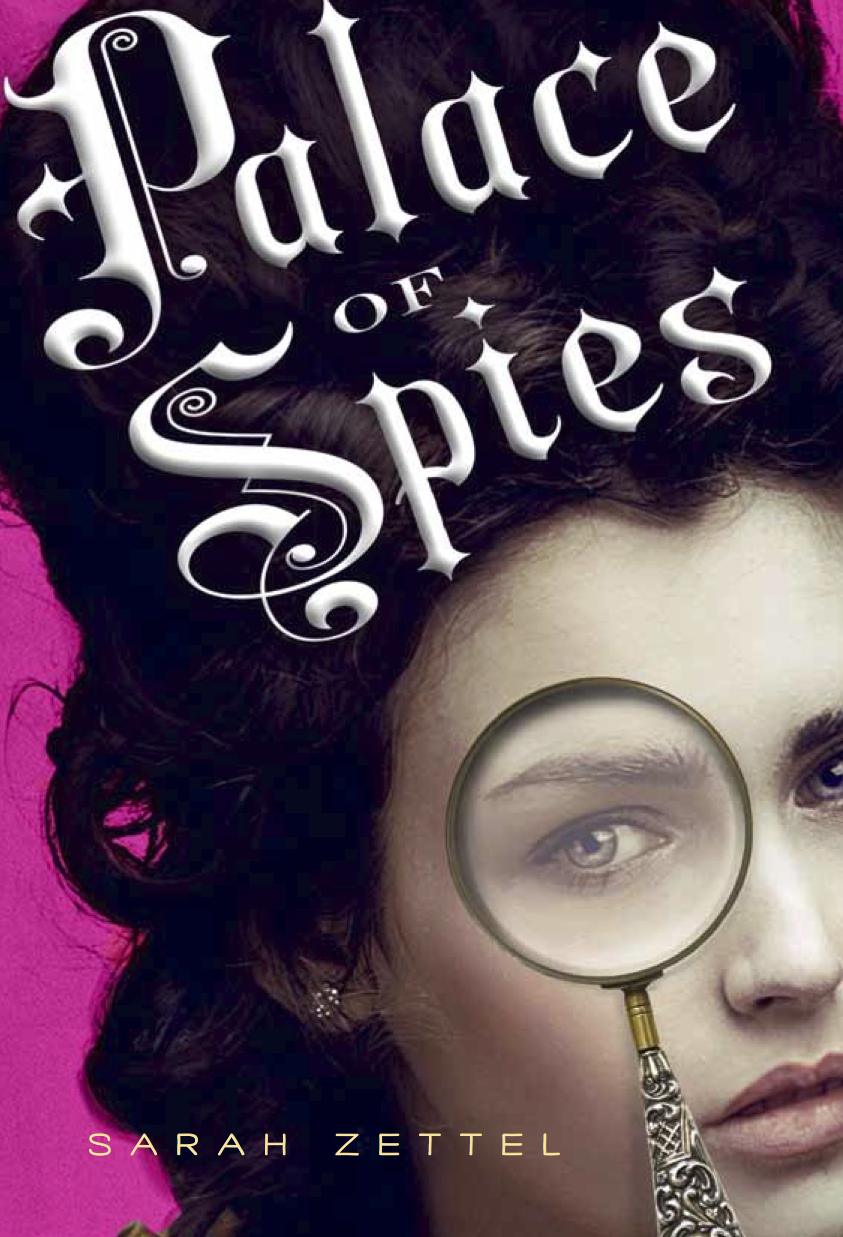

Palace of Spies

Being a True, Accurate, and Complete Account of the Scandalous and wholly Remarkable Adventures of Margaret Preston Fitzroy, counterfeit lady, accused thief and confidential agent at the court of His Majesty, King George I.

###

CHAPTER ONE

London, 1716

In which a dramatic reading commences, and Our Heroine receives an unexpected summons.

###

I must begin with a frank confession. I only became Lady Francesca Wallingham after I met the man calling himself Tinderflint. This was after my betrothal, but before my uncle threw me into the street and barred the door.

Before these events, I was simply Margaret Preston Fitzroy, known mostly as Peggy, and I began that morning as I did most others — at breakfast with cousin Olivia, reading the newspapers we bribed the housemaid to smuggle out of Uncle book room.

“Is there any agony this morning?” asked my cousin as she spread her napkin over her flowered muslin skirt.

I scanned the tidy columns of type in front of me. Uncle Pierpont favored The Morning Gazetteer for its tables of shipping information, but there were other advertisements there as well. These were the “agony columns;” cries from the heart that some people thought best to print directly in the paper, where the object of their desire, and everybody else, would be sure to get a look at them.

“‘To Miss X from Mister C.,” I read. “The letter is burnt. I beg you may return without delay.’”

“A Jacobite spy for certain,” said Olivia. “What else?”

“How’s this? ‘Should any young gentleman, sound of limb in search of employment present himself at the warehouse of Lewis & Bowery in Sherwood Street, he will meet a situation providing excellent remuneration.’”

“Oh, fie, Peggy. How dull.” My cousin twitched the paper out of my hands and smoothed it over her portion of the table.

As I know readers must be naturally curious about the particulars of the heroine in any adventure, I will here set mine down. I was at this time sixteen years of age, and in what is most quaintly called “an orphaned state.” In my case, this meant my mother was dead and no one knew where my father might be found. I possessed dark hair too coarse for fashion, pale skin too prone to freckle in the sun, and dark eyes too easily regarded as “sly,” all coupled with a manner of speaking that was too loud and too frank. These fine qualities and others like them resulted in my being informed on a daily basis that I was both a nuisance and a disappointment.

As I was also a girl without a farthing to call my own, I had to endure these bulletins. As a result, I was kept at Uncle Pierpont’s house like a bad tempered horse is kept in a good stable. That is, grudgingly on my uncle’s part, and with a strong urge to kick on mine.

“Perhaps its a trap.” I poured coffee into Olivia’s cup, and helped myself to another slice of toast from the rack. I will say, the food was a point in favor of my uncle’s house. He was very much of the opinion that a true gentleman kept a good board. That morning we had porridge with cream, toast with rough cut marmalade, kippered herrings, and enough bacon to feed a regiment. Which was good, because that regiment, in the form of all six of Olivia’s plump and over-groomed dogs milled about our ankles making sounds as if they were about to drop dead of starvation. “Perhaps the young man who answers the advertisement will be tied in a sack and handed to the press gangs.”

“There’s a thought. They might be slavers and mean to sell him to the Turks. The Turks are said to favor strong young English men.”

It is a tribute to Olivia’s steadfast friendship that my urge to kick never extended to her. My cousin was one of nature’s golden girls, somehow managing to be both slim and curved even before she put on her stays. She possessed hair of an entirely acceptable shade of gold, and translucent skin that flushed pink only at appropriate points. As if these were not blessings enough, she had her father’s fortune to dower her and a pair of large blue eyes designed solely to drive gallant youths out of their wits.

Those same gallants, however, might have been surprised to see Olivia leap to her feet and brandish an invisible sword.

“Back you parcel of Turkish rogues!” she cried, which caused the entire dog flock to yip and run about her hems, looking for something very small they could savage for their mistress’s sake. “I am a stout son of England! You will never take me living!”

“Hurray!” I applauded.

Olivia bowed. “Of course, Our Hero kills the nearest ruffian to make his escape, the rest of the gang pursues him, and he is forced to flee London for the countryside…”

“Where he is found dying of fever in a ditch by the fair daughter of Lord…Lord…”

“Lord Applepuss, Earl of Stemhempfordshire.” Olivia scooped up the stoutest of her dogs and turned him over in her arm so she could smooth his fluff back from his face and gaze adoringly down at him. “Lady Hannah Applepuss falls instantly in love, and hides Our Hero in a disused hunting lodge to nurse back to health. But Lord Applepuss is a secret supporter of the Pretender, and he means to marry his daughter off to a vile Spanish noble in return for money for another uprising…”

“And as she is force aboard a ship to sail for Spain, he steals on board for a daring rescue?” One of the dogs decided to test out its savaging skills on my slipper. I gave it a firm hint that this was a bad idea with the toe of that self-same slipper. It yipped and retreated. “Can there be pirates?”

“Of course there are pirates.” Olivia nipped some bacon off her plate with her fingers. “What do you take me for?” She turned to the dogs and held the bacon up high so that they all stood neatly on their hind legs, and all whined in an amazing display of puppy harmony.

“You really should write a play, Olivia,” I said, addressing myself once more to my toast, coffee and kippers. “You’re better at drama than half the actors in Drury Lane.”

“Oh, yes, and wouldn’t my parents love that? Mother already harangues me for overmuch reading. ‘A book won’t teach you how to produce good sons, Olivia.’”

“That just shows she hasn’t read the right books.”

Olivia clapped her hand over her laugh. “You outrageous thing! Well, perhaps I shall write a play. Then…” But I never was to know what she would do then. For at that moment, the door opened and to our utter shock and surprise, Olivia’s mother entered.

My Aunt Pierpont declared she could not bear the smell of food before one of the clock, so she daily kept to her boudoir until that time. My throat tightened at the sight of her, and my mind hastily ran down a list of all my recent activities, wondering which could have gotten me into trouble this time.

My cousin, naturally, remained unperturbed. “Good morning, Mother. How delightful of you to join us.” Olivia possessed admirably tidy habits when it came to other people’s property and forbidden literature, and so folded the paper so its title could not be seen. “Shall I pour you some coffee?”

“Thank you, Olivia.” Aunt Pierpont had been a celebrated beauty in her day. She still carried herself very straight, but time and four babies had softened and spread her figure. Twenty-some years of marriage to my uncle had wreaked havoc upon her nerves and she was forever clutching at things; a handkerchief, a bottle of eau de toilet, an ivory fan. This morning it was the handkerchief, which she applied it to her nose as she drew up her seat next to mine.

“Good morning to you too, Peggy, I trust you are well this morning?”

“Yes, Aunt. Quite. Thank you for asking.” I slipped a glance at Olivia, who was busy pouring coffee and offering it to her mother with sugar and cream. Olivia shook her head, a tiny movement you wouldn’t catch unless you were looking for it. She had no notion what occasioned this unprecedented appearance either.

“Isn’t the weather fine today?” Aunt Pierpont’s hands fussed with her lacy little square, as if about to pull it to bits. “Olivia, I think a stroll in the garden will be just the thing after breakfast.”

This was too much for even Olivia’s composure. A flicker of consternation crossed her face. “Yee…es, certainly. We’d be glad to, wouldn’t we, Peggy?”

“Erm, no, my dear. I thought just you and I. Surely, Peggy won’t mind.”

“No, of course not.” My mind was racing. What could Aunt have to say to Olivia that I couldn’t hear? Surely Olivia hadn’t received a marriage offer? Her looks and her father’s money meant she had cartloads of youths chasing after her. Worry knotted in my stomach. What would I do in this house without Olivia? Uncle Pierpont often grumbled about sending me off to Norwich to “make myself useful” to his aging mother, thus saving himself the cost of my keeping.

“Well.” Olivia delicately blotted her mouth with her napkin. “Shall I fetch my bonnet, then?”

“Yes, yes, do.”

Olivia scurried from the room, the canine flock trailing behind. Left alone with my aunt and my now thoroughly queasy stomach, I found it difficult to fit any words to my tongue.

“Peggy, you know we are all very fond of you.” Aunt Pierpont squeezed the much abused handkerchief in her fist.

“Yes, Aunt.” I found myself staring at that strangled bit of lace, and fancied it might soon yield some milk, or a plea for help.

“And we’ve always had your welfare at heart.”

This is it. I am bound for Norwich, and a damp cottage and a deaf old woman who can pinch a sixpence until it screams. I’d been there once before, one interminable, gray winter to nurse the Dowager Pierpont through a cold. She’d made up her mind that if she was to have nothing but gruel and weak tea, no one else need have anything better. I must have written down a thousand murder plans in my diary in those months. Had her serving girl been able to read, I would have been hanged straight away.

“I was very fond of your mother,” my aunt added suddenly. “You have grown to be very like her, did you know that?”

“No.” In fact, she never spoke of my deceased mother. No one did.

Aunt Pierpont gave the handkerchief a fresh twist. “Well you have. Just as pretty, and just as willful. You must…” she bit her lip and another ripple of fear surged through me. But before she could force another word out, the door opened to admit Dolcy, the parlor maid.

“I beg your pardon, Ma’am,” Dolcy bobbed her curtsey to us. “But master says Miss Fitzroy is to join him in his book room.”

So, the end had come. I rose to my feet. My aunt smiled encouragingly at me and gave my hand a limp pat. Norwich. Empty. Gray. Flat. With a vicar whose sermons lasted a full two hours every Sunday and Thursday. My stays squeezed my breath, making me unpleasantly light-headed as I walked to the door. No books in the cottage, no hearth in my bedroom…

Olivia stood in the dim hallway, bonnet dangling in her fingers.

“I heard everything.” She seized my hand at once. “What have you done? Tell me quickly.”

“Nothing, I swear.” We were due to attend Lady Clarenda Newbank’s birthday party that evening. I didn’t care for Lady Clarenda nor she for me, but the party would provide a welcome change of scene. Because of this, I had been treading very gently around my uncle so he should not be tempted to forbid my going.

“Hmmm.” Olivia frowned. “Well then, it’s probably something trifling. About expenses, perhaps.”

Neither one of us believed her, especially with her mother waiting to have some urgent, private conversation in the gardens. I walked the narrow, dark corridors to my uncle’s book room, and found myself wondering it felt to walk toward a trap one knew was coming. Unfortunately, unlike Olivia’s imaginary hero, I had no way to fight back.

#

The dominant feature of my uncle Pierpont’s book room was his desk. I had never once been in this room when the great ledger was not open on that gleaming surface, accompanied by bulwarks and battlements of letters and documents sealed with all colors of ribbon and wax.

Uncle Pierpont himself was a skinny man. He had a skinny legs beneath his well cut breeches and silk stockings. His arms had knobby elbows that always looked ready to poke through the cloth of his coat. The clever fingers of his hands seemed made for counting and writing sums. Slitted eyes graced his long face on either side of a nose at least as sharp as his pen. When I walked in, he was bent so close over his ledger, you might have thought he was using his nose rather than the goose quill to write out his accounts. His short-queue wig, a bundle of powered curls, clung to the top of his head at most a dangerous angle.

I was determined to remain calm and resolute, but that room and The Desk had some magical power to them. By the time I crossed the long acre of carpet to stand in front of Uncle Pierpont, I was once again eight years old; alone, poor, terrified, and trying desperately not to fidget.

The great clock in the corner ticked, and ticked. My uncle continued his laborious writing without once glancing up. I valiantly battled against fidgets, against fear, and against wondering what uncle would do when his wig slipped off his shiny forehead, which it surely must at any moment.

Finally, Uncle Pierpont finished his column and lifted his nose from the page. “Ah, there you are at last.”

“Yes, Sir,” I replied meekly. The quickest way through these interviews was to agree with whatever was said.

“I have some good news for you, Peggy.” Uncle Pierpont plucked a sheaf of documents bedecked with ribbons and red wax seals off one of his paper battlements.

“Good news? Sir?”

“Yes.” Uncle Pierpont pushed the documents across the desk toward me. “You are betrothed.”